“Freedom isn’t the road. It’s the courage to keep driving when you don’t trust the engine.”

Week 1 – Leaving Bregenz

The lake was still half-frozen when I packed the van. The T4 started only on the third try — a coughing protest, then the low diesel growl I’ve come to love. I told myself: if it runs, I go.

Day 2: Arlberg Pass, drizzle turning to sleet. The heater barely works. The dashboard light flickers like a heartbeat I don’t trust. I slept near Bludenz, engine off, wrapped in two blankets. Woke at 3 a.m. certain I’d heard footsteps. Just snow sliding off the roof.

Day 5: Innsbruck. Changed the oil, bought new wiper blades. The mechanic called the van “a museum piece.” I laughed but felt defensive, like he’d insulted a friend. By week’s end I’d crossed into Switzerland, the Alps rising behind me. The road curved like a promise and I believed it — for now.

Week 2 – Lake Geneva to Dijon

The van’s temperature gauge climbed past normal near Lausanne. I pulled into a rest stop; steam hissed from under the hood. A man in a red delivery uniform helped me top up coolant. He said, “Elle a besoin de patience, cette voiture.” I said, “So do I.”

I camped that night above Lake Geneva. Lights of Montreux shimmered below. First real moment of quiet. Then rain drummed the roof and wouldn’t stop for two days.

Saturday: met Clara, a Swiss painter, in a laundromat. We drank bad coffee while our clothes spun. She said she once drove to Portugal in a van “to learn how silence sounds.” She drew a small mountain in my notebook and wrote: “Bonne route.” The van stalled leaving Dijon. A minute of panic before it caught again. I talked to it out loud for the rest of the drive.

Week 3 – Into France

Crossed into Burgundy vineyards. Spring here smells like earth and diesel. I keep the radio on low, half for company, half to mask strange rattles.

Midweek: exhaust pipe loosened. Found a roadside garage in Nevers — a father and son, grease to their elbows.

They tightened the bolts, refused payment, only asked for a selfie with “the Austrian woman and her brave van.” Before I left, the son said, “Pas trop vite — she likes to go slow.” I think he meant the van. Maybe both of us.

I sleep mostly in supermarket car parks now — more light, less fear. Still, every clang of metal makes me flinch. Freedom has an echo I didn’t expect.

Week 4 – Paris

Arrived outside Paris on fumes. The van sputtered, coughed, then died in a McDonald’s parking lot. I sat there laughing and nearly crying until a man knocked on the window. Étienne, 50-ish, drives a tow truck. He towed me to a small garage near Nanterre and waited while they checked the fuel pump. When it was clear I’d be stuck overnight, he brought croissants the next morning. We ate sitting on the curb beside the van.

He talked about his daughter who’d moved to Canada, how he admired “women who go alone.” When I left, he said quietly, “Ne laisse pas la peur conduire.” Don’t let fear drive. I told him I’d try. The van started again, reluctantly. I crossed the Seine at sunset, city lights trembling on the water, the engine ticking like an old clock that refuses to stop.

Week 5 – Loire to Bordeaux

The van is coughing again. I can feel the hesitation in third gear, the small tremor before the engine catches. Every hill feels like a test of loyalty — mine or the van’s, I’m not sure which.

I’ve started talking to it more. Not just the usual coaxing, but full conversations: “You and me, we just have to get to the coast,” I say aloud. When the gearbox groans in reply, I take it as understanding.

Stopped overnight outside a vineyard near Tours. In the morning, the owner came out — grey-bearded, wool sweater despite the heat. He introduced himself as Luc. Said he’d once had the same model van. We talked about engines, vines, and weather patterns over instant coffee made on my small camping stove. When I left, he gave me a bottle of his wine “for when the road behaves.” I haven’t opened it yet — I’m saving it for when the van truly scares me.

By Friday, I reached Bordeaux. The river was brown and slow; the air smelled like wine and metal. I parked under plane trees, listened to young people laughing by the quay, and felt both invisible and comforted by the sound.

Week 6 – Near Bayonne

I can tell the van hates cities. Every red light, every stop-and-go, makes it wheeze.

Monday morning, it refused to start altogether. Battery flat. A local mechanic named Élodie jump-started it and said the alternator is “half-dead.” Half-dead — I know the feeling.

She offered to order a replacement part, but it would take five days. I spent those days parked near a surf town outside Bayonne. Windy, kind of wild. Met a man named Adrien who carved surfboards in a small shed near the beach. We spoke over beers, the kind of half-conversation that happens when you both understand and don’t. He asked if I was lonely. I told him sometimes the road feels like company. He said, “That’s how the ocean feels too.” When I left, the van started immediately — as if jealous.

That night, I reached the border. I could smell the salt of the Atlantic. Spain was a line of lights across the hills.

Week 7 – Crossing into Spain

The moment I crossed the border, everything changed: the rhythm of speech, the sunlight, even the smell of fuel. The van seemed lighter too, though the steering still pulls right.

San Sebastián appeared like a dream after so many quiet roads. I parked on the hill at Monte Igeldo with other vans, facing the bay. The air was thick with grilled fish and music from beach bars.

There I met Isabela, a teacher from Madrid traveling alone in a small camper. We shared dinner — tinned lentils and cheap wine — and stories about leaving things behind. She said, “People think we’re brave, but really we’re just tired of waiting for someone else to come.” We laughed, and for the first time in weeks, I felt unafraid.

But that night, the van alarm went off by itself. No one around. I checked the locks twice. Maybe it was the wind. Maybe not.

Week 8 – Basque Country Roads

Headed west along the coast — narrow roads, cliffs dropping to the sea. The van overheats on long climbs. I carry water jugs now, just in case.

Stopped in a small town called Zumaia to cool the engine. A young mechanic, Diego, helped flush the radiator and refused payment. He said, “Old cars are like people. They just need to be listened to.”

I think about that as I drive. I’ve started hearing phantom noises — or maybe real ones — a new rattle from the back, a hiss that wasn’t there before. Every sound makes my pulse jump.

Parked tonight above a cove. Wind shaking the van gently. Somewhere below, waves crash against rocks, steady as breathing. I haven’t opened Luc’s wine yet. Maybe when I cross into Portugal. Maybe when I stop being afraid every time the engine hesitates.

Week 9 – Across Castile

The air inland is dry and pale. I left the Basque coast behind and followed empty roads through rolling wheat fields and villages where the cafés all close for siesta. The van hates the heat; the temperature gauge creeps toward red every climb.

In a town called Soria the clutch pedal went soft. I coasted into a workshop that looked abandoned until a boy appeared wiping his hands. He bled the clutch line, said “ya está, señora”, and wouldn’t take money. I bought him cold Coca-Cola instead.

At night I parked outside a petrol station, the hum of trucks like lullabies. I keep thinking of Isabela from San Sebastián—how easily she laughed in the dark. Loneliness is a shape that keeps changing, but it never disappears.

Week 10 – Into Extremadura

The road south flickered between dust and olive trees. The van rattled like an old train. Somewhere before Cáceres the fan belt screamed and snapped; I pulled over under a cork oak. It was forty degrees.

A shepherd walking by phoned his cousin who ran a small garage. They arrived an hour later in a pickup, fixed the belt on the shoulder. When I thanked them, the older man said, “No road is friendly when you stop moving.”

That night I opened Luc’s wine from France. Warm, rough, but it tasted like endurance. I wrote in the notebook: If I make it to the ocean again, I’ll forgive the van anything.

Week 11 – Crossing into Portugal

Border came and went—just a sign and a softer light. The landscape turned green again. I stopped at a roadside café; the owner’s dog slept in the doorway. I ordered café pingado and the woman smiled when I tried to repeat it.

The van groaned on steep descents toward the coast. I could smell the Atlantic long before I saw it. At last, near the end of the week, the map said Praia da Areia Branca.

A small village: white houses, blue shutters, salt crusted on every window. I parked beside a row of fishing boats pulled up onto sand.

Week 12 – Praia da Areia Branca

The first morning here the van refused to start. I was too tired to be angry. I just sat on the step, watching early surfers run across the sand with their boards underarm, wetsuits half-zipped. The air smelled of salt and sunscreen, the kind of coastal morning that feels timeless.

A man from the surf school next door noticed me lifting the van’s hood. He wandered over barefoot, holding a wax comb and a mug of coffee. His name was Miguel — lean, sun-faded hair, smile like he’d spent a lifetime squinting into sunlight.

He asked if I needed help, and without waiting for an answer, leaned in to check the cables. “Loose ground,” he said after a moment. “Common with old vans. They just need attention.” He tightened the bolt with a small wrench he fetched from his workshop — a low shed stacked with surfboards, each at a different stage of sanding and glassing.

When the van finally turned over, he gave a small triumphant shout: “Velha, but loyal!” I stayed a few days longer than planned. I parked near the dunes, wrote in the evenings while watching surfers cut across slow Atlantic waves. Miguel would wander by with bread or a couple of beers, sit by the van, talk about the rhythm of tides and the winter storms that carve the beach into new shapes each year.

He said, “The sea fixes what people break — but not always the same way.” When I told him I’d soon move on, he nodded as if he’d known from the start. “Road people,” he said, “and wave people — we never stay.” When I left on Sunday morning, the wind was offshore and the surf perfect. Miguel waved from the breakwater, a board under his arm. The van started easily, humming like it wanted me to go while I still could. I kept one of his wax combs on the dashboard — a small piece of proof that I’d been there, that something real had happened in that week by the sea.

Week 13 – Lisbon

City after the beach feels too loud, too tight. I park under eucalyptus trees on the outskirts, where the air smells of resin and petrol. The van leaks oil now — small dark coins marking every stop.

Lisbon is hills and heartbreak in sunlight. I wander Alfama, eat sardines from paper plates, listen to an old man singing fado in a doorway. Every note sounds like leaving something behind.

At night I dream the van rolls down one of these steep cobblestone streets on its own. I wake sweating, check the handbrake twice.

Week 14 – Sintra to Porto

I drive north along the coast. Sintra’s forests are misted green, but the van hates the climbs. The clutch smells of burning. I baby it in second gear, whispering, “Just a little more, old friend.”

In Nazaré, I watch waves taller than houses and feel very small. The surfers there chase monsters. I think of Miguel, wonder if he’s out in this water now.

Porto surprises me. The river, the bridges, the wine-dark light. I find a cheap campsite outside the city where other van-lifers gather — Germans, Norwegians, a couple from Slovenia. For two nights we share food and laughter. It feels like community, but I know it’s temporary. We are all moving, always moving.

Week 15 – North Portugal: The Breakdown

The van dies just before the Spanish border. Complete silence. No warning.

I sit on the roadside near Viana do Castelo, heat rippling off the asphalt. A trucker stops, helps me push the T4 onto the verge. He calls a local mechanic. The diagnosis: blown head gasket.

The man shakes his head: “Too old. Too expensive.”

For the first time, I consider leaving the van behind. I even picture myself on a train, small bag, no engine to worry about. But when I sleep that night inside it, the walls creak like breathing. I can’t abandon something that has carried me so far.

The mechanic finds a used part from another T4. Three days of waiting, sweating, second-guessing. Then it runs again — rough, but alive. I drive north before it can change its mind.

Week 16 – Galicia

Crossed into Spain under grey skies. Everything smells of eucalyptus and rain. Galicia is green and haunted — cliffs, fog, sudden churches in the mist.

In a fishing village near A Coruña, a woman sells me hot empanadas from her kitchen window. She calls me “valiente,” brave. I don’t feel brave. I feel tired and strange, like the sea has soaked into my bones.

At night I park on a headland. The wind is fierce. I wonder if I’ll ever stop listening for mechanical ghosts in the engine — the sounds that tell me how close I am to being stranded again.

Weeks 17–20 – The Long Heat

August blurs. South through León, east toward the Pyrenees. The van’s fan squeals. I drive with the windows down, the air like an oven.

I meet other travelers — mostly young, mostly fearless. They treat me like some kind of veteran. Maybe I am. I’ve learned to sleep anywhere, fix small things, keep fear folded neatly at the back of my mind.

But the solitude sharpens. In empty parking lots I sometimes imagine another set of footsteps. Not danger, exactly — just the echo of all the people I’ve met and left behind.

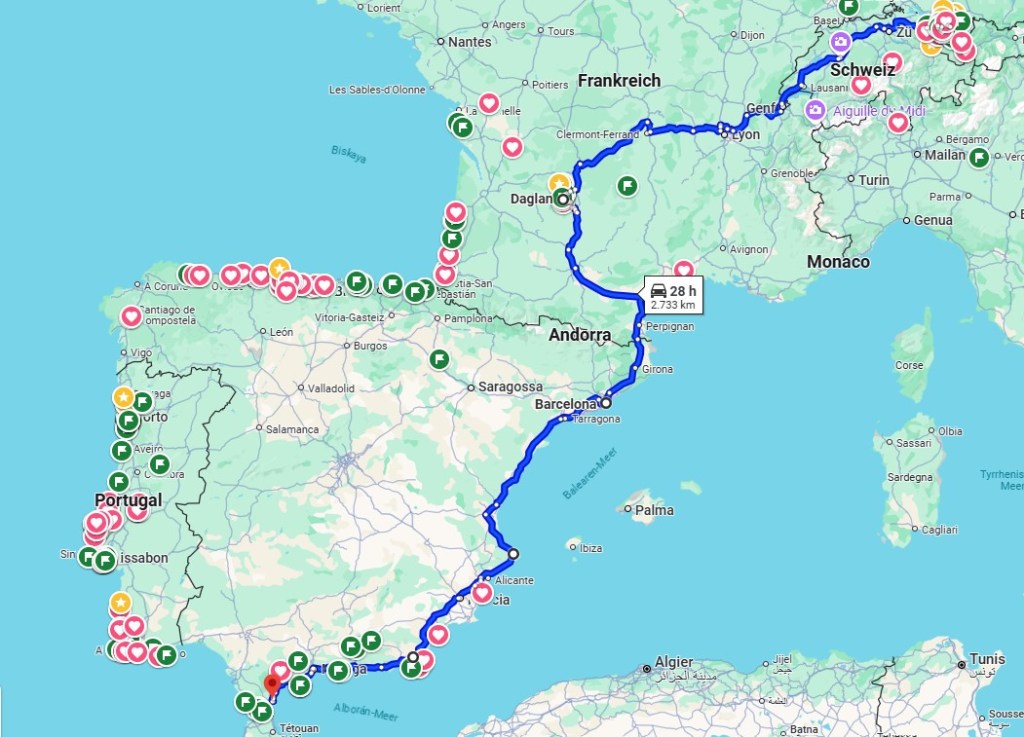

Weeks 21–24 – Across the Pyrenees

September brings rain again. I crawl through mountain passes, mist thick as milk. The T4’s wipers quit halfway down a descent. I drive with one hand out the window, wiping the glass with a rag at every turn.

Somewhere near Andorra, I pass a mirror in a café and barely recognize myself — hair wild, skin burnt, eyes alert like a stray animal. I write: “I don’t know if I’m changing, or just revealing what was always there.”

Weeks 25–28 – Back Through France

Bordeaux again, then east toward Lyon. Roads familiar but different — like meeting an old friend after too long. The van rattles, but the sound has become background music.

In one small town, the starter fails. An elderly woman from a nearby house lends me her tools. We talk about her husband who used to fix tractors. She laughs when I manage to get the van going.

She says, “Les vieilles machines… elles aiment les mains patientes.” Old machines like patient hands.

I drive on, feeling strangely proud.

Weeks 29–31 – Back to Austria

The first snow dusts the Alps. The van wheezes climbing the Brenner Pass. Crossing back into Austria, I feel an ache I can’t name — relief, sadness, maybe both.

Bregenz appears one cold morning, lake grey and flat. I park where I started eight months ago. The same space. The same van. A completely different person.

Week 32 – November: Home

I unpack slowly, as if movement itself has weight. The van sits outside my small apartment, oil-stained but dignified.

People ask if I found what I was looking for. I never know how to answer. I think of the endless roads, the faces of Clara, Adrien, Isabela, Miguel. Of nights I thought the engine’s last breath would be mine too. Of mornings when starting it felt like a small miracle.

I write one last line in the notebook:

“Freedom isn’t the road. It’s the courage to keep driving when you don’t trust the engine.”

Then I close the journal. The van rests in silence, smelling faintly of diesel and sea salt.

Next stop on my little road trip was Tarifa in Spain, than Gibraltar